WORKING IN STONE

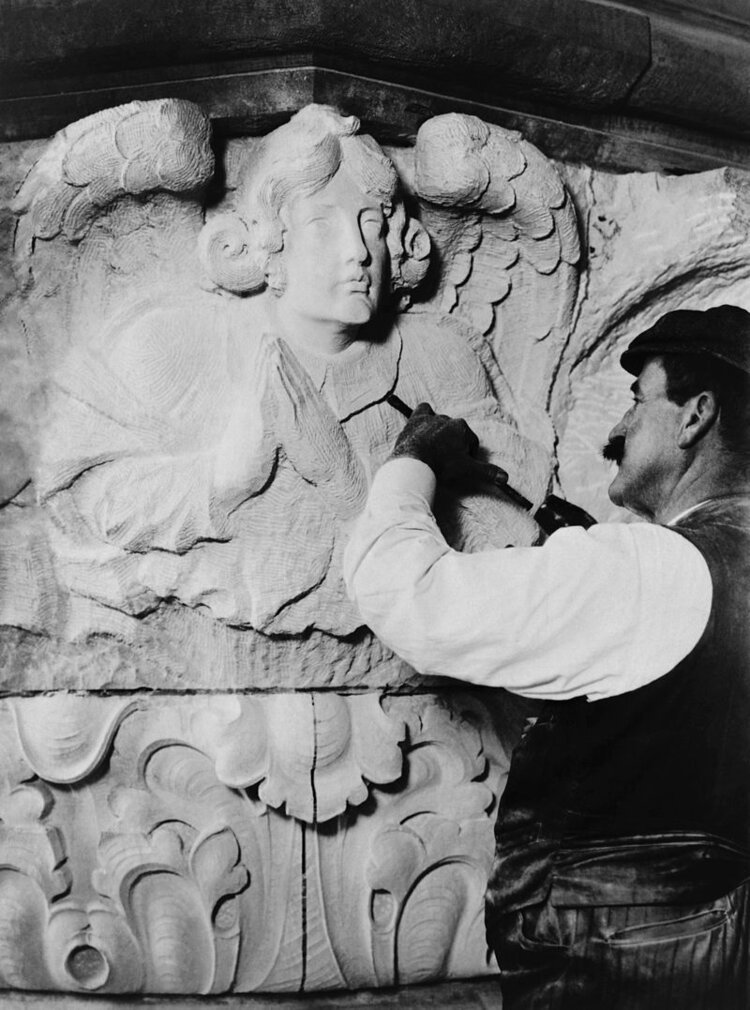

Stone carver carving stone, at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York, 1909.

Oral historian and radio broadcaster Studs Terkel’s book Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do, explored how Americans viewed their jobs. Published in 1974, Terkel interviewed over one hundred people whose working days went from the cradle to the grave literally, including a baby nurse and a gravedigger. Along the way, Terkel interviewed a stonemason, Carl Murray Bates, who spoke of stone’s siren call.

Working: people talk about what they do all day and how they feel about what they do

by Studs Terkel

Bates started in the trade when he was seventeen, and at fifty-seven, he reflected on the endurance of stone: "Immortality as far as we're concerned. Nothin' in this world lasts forever, but did you know that stone—Bedford limestone, they claim—deteriorates one-sixteenth of an inch every hundred years? And it's around four or five inches for a house. So that's gettin' awful close." The stonemason also reflected on the timeless quality of his craft "Stone is still stone, mortar is still the same as it was fifty years ago. ....Automation has tried to get in the bricklayer. Set' em with a crane. I've seen several put up that way. But you're always got in-between the windows and this and that. It doesn't seem to pan out. We do have an electric saw. We do have an electric mixer to mix the mortar but the rest of it's done by hand as it always was.”

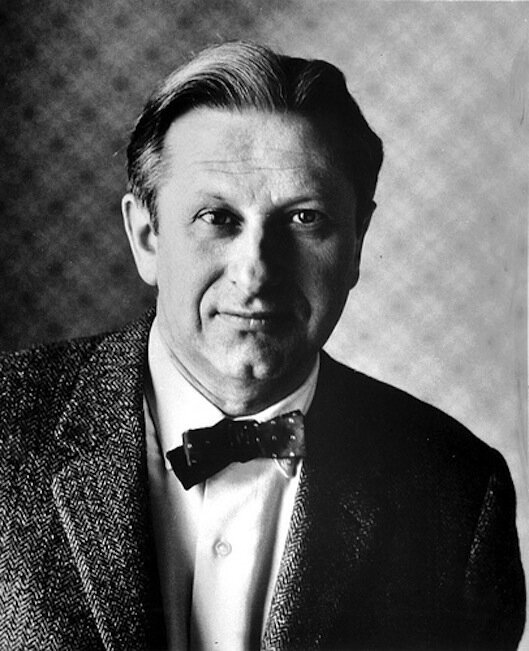

Studs Terkel, oral historian.

Ultimately Bates looked back over his work with pride and an appreciation for the fingerprint of the artisan, “There’s not a house in this country that I haven’t built that I don’t look at every time I go by. I can set here now and actually in my mind see so many that you wouldn’t believe. If there’s one stone in there crooked, I know where it’s at and I’ll never forget it. Maybe thirty years, I’ll know a place where I should have took that stone out and redone it but I didn’t. I still notice it. The people who live there might not notice it, but I notice it. I never pass that house that I don’t think of it. I’ve got one house in mind right now. That’s the work of my hands. ’Cause you see, stone, you don’t prepaint it, you don’t camouflage it. It’s there, just like I left it forty years ago,” he said.

Terkel, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, worked to preserve American Oral History. In addition to "Working," he wrote "The Good War: An Oral History of World War Two" and "Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression." He interviewed Americans across the country and socioeconomic spectrum to leave a permanent record of their thoughts and feelings.